This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. It was a bad week for Joe Biden who, according to the Wall Street Journal editorial board, wants to take Americans’ gas stoves away, and who appears to have left classified documents in his Corvette. Markets, oddly, don’t care about either story. Email us your conspiracy theories: robert.armstrong@ft.com & ethan.wu@ft.com.

An inflation cheat sheet

It was a nice change of pace yesterday: a consumer price index report that was mostly unsurprising and, judging by markets’ reaction, already priced in. That is not to say December’s CPI reading was insignificant. Its significance was that it confirmed trends we already suspected. So today we step back and ask what we know, and don’t know, about inflation. We’ve divided things up into three buckets, based on how strong the available evidence is.

High confidence

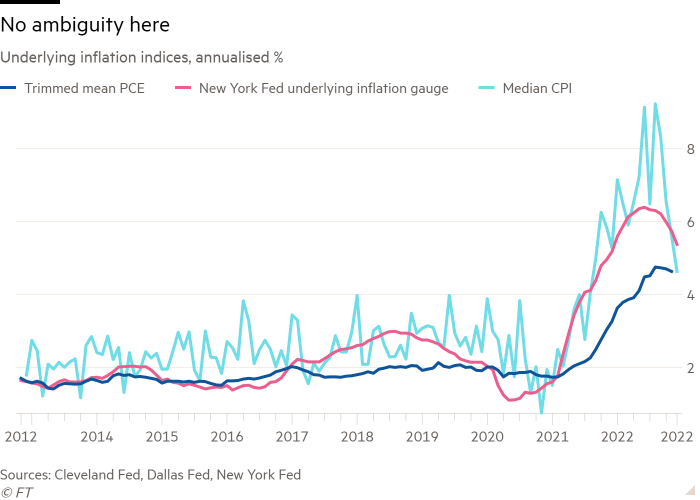

Inflation has peaked. Each of the last three cooler CPI reports has made a false dawn look less and less likely and now, barring external shocks, the pattern is definitive. The chart below shows several indices that measure the core trend of price pressures. The trimmed mean index, for example, excludes extreme price movements in both directions, while the underlying inflation gauge stirs together granular price data to find a common trend. They are all singing the same tune:

Shelter, the most influential inflation category, will cool later this year. To recap, official inflation indices capture new and existing leases, meaning they are more representative of real living expenses but slower to capture market turning points. But private indices of new leases, which reliably lead CPI by about nine months, show rent growth having peaked in the first half of 2022. Soon enough, CPI will follow.

Inflation expectations are under control. Whether you look at survey data, inflation break-evens or something else, the gist is the same. The New York Fed’s household survey illustrates the point. Though households still expect inflation to stay high for another year or so, three-year ahead expected inflation is in line with history:

Modest confidence

Core goods inflation is over. Goods have flipped to an inflation drag, thanks in no small part to falling car prices (mostly used cars so far, but CPI new car prices fell for the first time in December’s report). Overstocked retailer inventories and back-to-normal supply chains have helped too. Prices will probably keep falling for a while. For instance, Ian Shepherdson of Pantheon Macro notes new car prices are 20 per cent higher than their pre-pandemic trend would suggest. Still, with deglobalisation fears rampant, it’s an open question whether we’ll see a full snapback to the old-world trend.

Core services inflation is still too high. Just how high is sensitive to which bit of the data you focus on, though. The plainest comparison, using 3-month annualised rates, suggests core services inflation is at 6.1 per cent, versus an average of 2.5 per cent between the 2008 financial crisis and Covid-19. But because housing inflation will fall soon, this arguably overstates the problem. One could also gripe about including volatile airfares, deflationary health insurance prices or some other misbehaved component. This chart from Aneta Markowska of Jefferies shows a few choice cuts:

In all three cases, too high, but to different degrees.

Mysteries

Do wages need to sharply fall first for services inflation to unstick? Fed chair Jay Powell has made clear his answer is yes, because wages are a major cost that service businesses must pass on. Not everyone agrees. His detractors argue that what is keeping inflation sticky is not high wage growth itself, but high nominal consumption. Wage growth helps sustain high consumption, but so does job growth. And with payroll numbers and consumption now falling, perhaps wages are the wrong focus. Or maybe not! We’ve written about this debate a few times, but the main point is that smart people disagree about how wages feed into prices, and what the Fed’s order of operations should be.

How far and how fast will rent inflation decline? The shelter component is a formidable 42 per cent of core inflation, so the pace of rent deceleration matters, as does its steady-state inflation rate. If you need reason to worry, some have suggested that a catch-up effect in rent levels could spell higher-for-longer shelter inflation. Similarly, Omair Sharif of Inflation Insights flags a concerning re-acceleration in rents in New York and San Francisco. Mostly, though, we just don’t know. (Ethan Wu)

Are we heading for a corporate debt crisis? (Part 2)

Yesterday’s letter asked whether the rapid growth of low-quality corporate debt is a crisis waiting to happen. Much of this debt — a new paper from American for Financial Reform argues — is hard to track, poorly regulated and supervised, mislabelled, or owned by the wrong people.

We ended on the point that traditional measures of corporate indebtedness, which measure debt as a multiple of profits, look benign. But then the question “is there too much leverage?” is replaced by the equally unnerving “are very high corporate profits sustainable”? What looks like a manageable amount of debt looks very different when profits drop by, say, a third.

And boy oh boy do profits look high. We’ve written that public company margins are historically high, but the data from the national accounts shows that non-bank corporate profits have grown at twice the rate of GDP over the past five years.

The risk that high leverage might be obscured by abnormally high profits does not appear to be on the radar of the Fed, which has an implicit financial stability mandate. This is from the central bank’s latest Financial Stability Report:

Business debt-to-GDP ratio and gross leverage stood at high levels (although significantly lower than the record highs reached at the onset of the pandemic). In contrast, median interest coverage ratios continued to improve, bolstered by strong earnings, and have reached record highs. Taken together, vulnerabilities from business leverage appeared moderate.

Here is the coverage ratio chart from the report. It does seem pretty reassuring, so long as profits hang in there. I assume the ratio is calculated as operations earnings/interest expense:

The Fed is also not too worried about the effect of rising rates on corporate leverage:

The effect of rising interest rates was muted, as corporate bonds — which account for the majority of the debt of public firms — generally have fixed interest rates and longer-term maturities

This is true. But it does not mean that there is not a significant amount of variable rate debt running around the financial system. The Fed reckons there is $1.4tn in leveraged loans out there. That is a lot less than the $8.7tn in corporate bonds outstanding, but is still enough to make some trouble. On top of that there is, according to Preqin, about $1.4tn in privately issued debt globally — credit issued by private equity funds, hedge funds, and other non-banks. Most of this private debt is held in the US. Crucially, both leveraged loans and private debt tend to be floating rate.

Does the nearly $3tn in leveraged loans and private credit represent an impending crisis? No, but it is a pressure point. If rates rise and profits fall, this is the area that will feel the heat. The pressure could become acute if heavily indebted companies need to refinance while the economy is struggling.

Fans of high-yielding debt argue that most companies have wisely pushed their maturities several years into the future, beyond the likely duration of any Fed-induced recession. Here for example is a chart from an upcoming report from Goldman Sachs wealth management — leveraged loans are the green columns:

This should help avert trouble. But the core worry — that profits will mean-revert, making high leverage hard to bear — remains. Hope for a soft landing.

One good read

Why Disney gave Dan Loeb got the VIP treatment but Nelson Peltz got the cold shoulder.

Comments