‘Volatility vortex’ slams into $24tn US government bond market

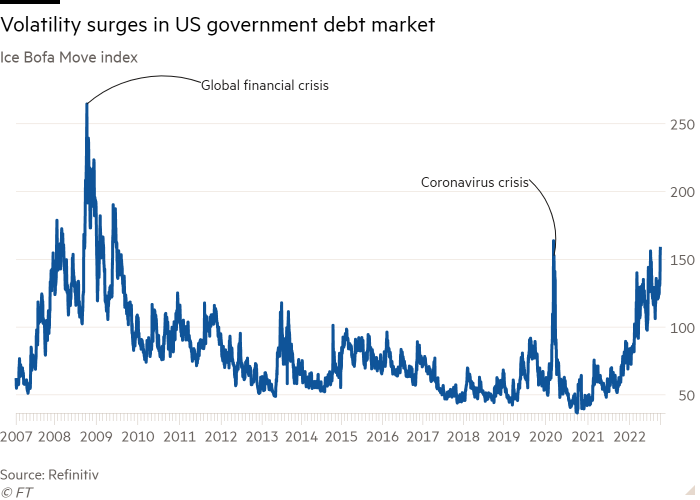

The $24tn US Treasury market has been hit with its most severe bout of turbulence since the coronavirus crisis, underscoring how big swings in international bonds and currencies and jitters over US rate rises have spooked investors.

The Ice BofA Move index, which tracks fixed income market volatility, has reached its highest level since March 2020, a time when deep uncertainty about how the pandemic would affect the world economy set off massive fluctuations in US government bonds.

“Right now it is all about market volatility,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, a strategist at TD Securities. “You have investors staying away because of the volatility — and investors staying away increases volatility. It is a volatility vortex.”

Fixed income investors’ nerves have been frayed by a series of events most commonly seen during market crises. Japan, the world’s third-biggest economy, last week stepped in to defend the yen after the currency rapidly tumbled to a 24-year low against the dollar. Just days later, plans for big tax cuts by the UK government ignited a historic sell-off in Britain’s currency and sovereign debt markets.

These international events have added to a powerful pullback in the US Treasury market that accelerated after the Federal Reserve last week delivered its third-straight 0.75 percentage point rate rise and signalled significantly tighter monetary policy to come.

The 10-year Treasury yield, a key benchmark for global borrowing costs, has surged to more than 4 per cent from 3.2 per cent at the end of August, leaving it set for the biggest monthly rise since 2003. It is on track for its sharpest ever annual rise. The two-year yield, more sensitive to fluctuations in US monetary policy, has leapt 3.55 percentage points this year, which would also mark a historic increase.

The big price movements have left investors wary of trading in a market that acts as the bedrock of the global financial system and is typically considered a haven during times of stress.

With investors on the sidelines, liquidity in the Treasury market — the ease with which traders buy and sell — has deteriorated to its worst level since March 2020, according to a Bloomberg index. Poor liquidity tends to exacerbate price swings, worsening volatility.

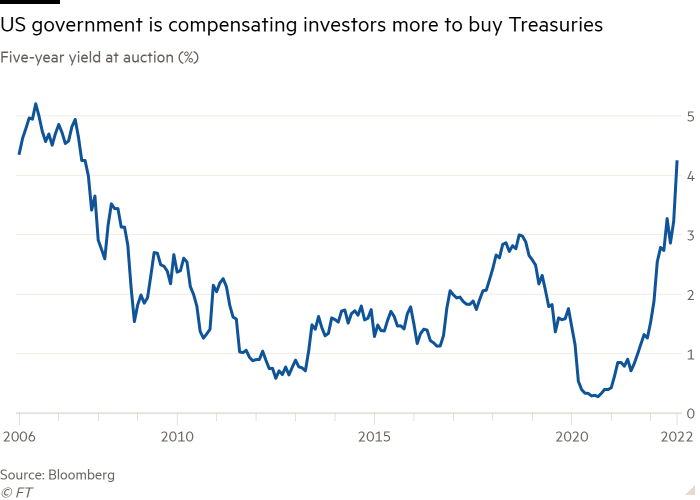

In a sign of how the fraught conditions are keeping some fund managers away, the US has drawn lacklustre demand at sales this week for a combined $87bn in new debt.

A two-year issuance on Monday priced at a high yield of 4.29 per cent, while a five-year deal one day later priced at 4.23 per cent — both marking the highest borrowing costs for the government since 2007.

The two-year debt was sold with the widest difference — or “tail” — between what was expected just before the auction and where it actually priced since the 2020 Covid-induced market ructions, said Tom Simons, a money market economist at US investment bank Jefferies.

The Treasury department will auction off $36bn in seven-year notes on Wednesday. The seven-year note has struggled to attract demand in less volatile moments, so the environment this week could pose a challenge.

“Until there is more certainty I think we will continue to have this ‘buyers’ strike,’” Simons said. “The markets are so crazy that it’s hard to price any kind of new [longer-dated bonds] coming into the market.”

A divergence between the Fed’s own outlook for interest rate and market expectations has added to the sense of uncertainty.

According to their latest projections, most Fed officials now expect the federal funds rate to rise from its current target range of 3-3.25 per cent to 4.4 per cent by year-end. By the end of 2023, Fed officials expect interest rates to stand at 4.6 per cent.

Meanwhile, investors are betting that the Fed will be forced to cut interest rates next year — with expectations in the futures market of a peak of 4.5 per cent in May of 2023, with a fall to 4.4 per cent by year-end.

Given persistent and broad-based price pressures, there is significant uncertainty about whether that amount of monetary tightening will be sufficient to bring inflation back down to the Fed’s 2 per cent target. Recession risks have also risen markedly, further clouding the outlook.

Strong rhetoric adopted by Fed officials about the central bank’s battle against inflation has stoked further angst in the market. Many officials now agree that interest rates need to rise to a level that actively constrains the economy and stay there for an extended period.

“The only other time I have seen us this united was at the beginning of the pandemic, when we knew we had to act boldly to support the economy through the pandemic and through the downturn,” said Neel Kashkari, president of the Minneapolis branch of the Fed, in an interview with the Wall Street Journal on Tuesday.

“We are all united in our job to get inflation back down to 2 per cent, and we are committed to doing what we need to do in order to make that happen.”