The mystery of how quantitative tightening will affect markets

June was not a great month to be a fund manager.

Global stocks fell 8.8 per cent, the second-biggest drop in a decade. Bonds, meanwhile, are on track for the worst year since 1865.

The bludgeoning came from several directions — first the rapid ascent of interest rates and then rising fears of a recession in the US. But some investors say another factor was also at play: the world’s most powerful central bank has yanked away its safety net.

Since 2008, fund managers in stocks, bonds and everything in between have known that by their side, the US Federal Reserve has been buying debt as part of its programme of economic support that kicked in after the financial crisis.

When Covid struck, the Fed souped up this so-called quantitative easing scheme to rescue markets from the brink of disaster, helping to fuel a huge rally in everything from government bonds to crypto tokens.

Now, though, soaring inflation has cornered policymakers into aggressively raising interest rates. In turn, this has bumped them into cutting back their vast stashes of assets — a process that the Fed kicked off early last month.

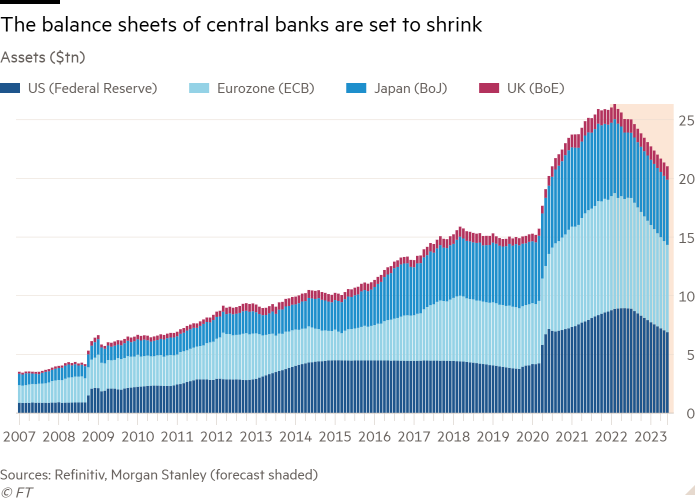

Along with the Bank of England and the European Central Bank, the Fed plans first to stop reinvesting maturing assets, and some economists think they may eventually outright sell some of what they have on their books. All told, the balance sheets of the heaviest-hitting central banks will shrink by roughly $4tn by the end of next year, according to estimates from Morgan Stanley.

The reversal is now well under way: just last week, its balance sheet shrank by roughly $20bn. And investors say it is already starting to hurt.

“Liquidity is driven by central banks,” says Guilhem Savry, who works in cross-asset solutions at Swiss asset manager Unigestion. “Over the past 10 years there has been large liquidity in the US and everywhere else, and now investors know it’s finished. It’s over.”

As a result, getting transactions done is becoming harder, Savry says, and speculative trading strategies have suffered “an end to the music”. But the added spice to this process is that like most other investors, Savry says he has no clear notion of how quantitative tightening — the tongue-twisting name for the process of balance sheet reduction — will affect markets.

“We haven’t seen the full impact yet. We don’t know the full detail,” he says. “But we do know the direction and it’s negative.”

The best and worst of times

The era of central bank asset-buying began in 2001, when the Bank of Japan instituted the policy in a bid to stimulate the country’s languishing economy while benchmark rates were already close to zero.

From the fringes of the monetary policy toolkit, the practice moved to the mainstream in 2008, when the Fed, BoE and later the ECB established their own bond-buying programmes in response to the crisis that engulfed the global financial system.

Through large-scale purchases of government securities, the central banks helped to push up the amount of reserves sloshing around the financial system. The aim was to encourage banks to increase their lending to households and businesses to a degree that would encourage spending, investments and other activities to help ignite growth.

Some economists have always been uneasy with QE for a variety of reasons, including a concern that it leads to central banks having too large a footprint in financial markets, potentially distorting the process of how assets are priced.

But the severity of the economic impact from the outbreak of the Covid pandemic in 2020 outweighed any concerns. The Fed began unlimited purchases of Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities, and ventured into facilities that enabled purchases of corporate bonds and municipal debt for the first time.

The ramp-up in scale and range of QE in 2020 compared to 2008 was “completely insane”, says Tatjana Puhan, deputy chief investment officer at French asset management group Tobam.

Over the course of two years, the Fed snapped up some $3.3tn in US government bonds and $1.3tn in agency mortgage-backed securities. As of March, that left the US central bank owning a quarter of all outstanding Treasury debt and a third of agency MBS.

The ECB and BoE each own just shy of 40 per cent of their government bonds, while the Bank of Japan, which is unique in having no intention of stopping its purchases, already owns nearly half of Tokyo’s outstanding government debt.

As well as expanding the monetary base, official asset purchases also crowd commercial investors out of the world’s safest assets, and force them to support riskier parts of the economy that might otherwise struggle.

But more than a decade of global QE has rewritten the rules for investors of all types. While central banks helped to bolster bond prices and crush their yields down to zero, or even below, fund managers were effectively pushed into taking ever greater risks to deliver the returns that their end investors expected.

“It has been the best of times and the worst of times for fund managers,” says David Riley, chief investment strategist at BlueBay Asset Management in London. “It was hard to blow up. A few did, but you had to work hard at it. In credit, you had just a relentless search for yield. You could look at a [corporate bond] and buy it because the ECB was going to buy it, even if your credit analysts were saying they didn’t like the fundamental story.”

This has dulled many investors’ capacity for assessing what shares and bonds are really worth, says Rob Almeda, global investment strategist at MFS Investment Management.

“One of the purposes of financial markets is to price risk. We allocate resources accordingly,” he says. “But we’re not pricing risk any more.”

Uncharted territory

Investors have known the unwind has been coming for months, and a grim first half to the year for most areas of financial markets suggests at least some of the impact has already been baked in to asset prices.

But a rundown process by several key central banks at the same time has never been seriously tested before. The Fed staged a dress rehearsal for QT beginning in 2017, gradually shrinking its balance sheets in a process then Fed chair Janet Yellen said would be so predictable it would be like “watching paint dry”.

In fact it ended up having to be abandoned after September 2019 when the plumbing of the financial system gummed up and overnight borrowing costs skyrocketed.

This time, no one, not even the Fed itself, really knows how it will work. “I’ve spent time with people way smarter than me on this,” says Kate El-Hillow, chief investment officer at Russell Investments, in an effort to determine whether the flow of asset purchases matters most, or the total on the Fed’s balance sheet, and what it might all mean for the rate at which new government bonds hit the market. She is no closer to certainty. “I don’t have a good read on how it will all play out,” she says.

Efforts to quantify exactly how QT will affect financial markets are complicated by several factors.

First, the Fed’s plans to shrink its balance sheet are much more aggressive than the 2017 attempt. By September, the Fed is aiming to ramp up the pace at which it is scaling back its portfolio to a maximum speed of $95bn per month, split between $60bn of Treasuries and $35bn of agency MBS.

That is double the pace the Fed targeted in its two-year experiment that began in 2017, after the global financial crisis, and the central bank will reach its maximum rate much faster than last time.

Treasury bills, which mature in one year or less, will also serve as a filler, meaning the Fed will cull its holdings of the short-dated debt whenever the amount of maturing longer-dated bonds falls short of the monthly cap.

The biggest wildcard is what the Fed will do about its holdings of agency MBS and whether the central bank will become an outright seller, as a number of top officials have hinted may be necessary. This would be an unprecedented move, and would spark fear about the markets’ ability to absorb the new debt launched into the market.

Another unknown is just how potent a monetary policy tool quantitative tightening actually is. Jay Powell, the Fed chair, emphasised that point recently, stressing the uncertainty that belies any estimate about its potential effect.

Still, Fed officials and researchers have offered up rough estimates. According to a June study published by the Fed, a $2.5tn drawdown in the balance sheet over the next few years would be roughly in line with just over a half-point increase in the benchmark US policy rate — a range in keeping with Fed vice-chair Lael Brainard’s assessment that the central bank’s plans amount to “two or three additional rate hikes”.

These forecasts underestimate the potential impact, says Solomon Tadesse, head of North American quant research at Société Générale. Instead, he projects $100bn in run-off would tighten policy by 0.12 percentage points, with the effects amplifying as the balance sheet shrinks further.

In separate research, strategists at Morgan Stanley counter-intuitively found that US bond yields tended to fall during the previous episode of quantitative tightening as prices rose — a conclusion they said was “not a typo” and attributed in part to economic growth patterns.

“This is clearly a complicated story, where balance sheet change is just one of many factors which impact cross-asset performance,” they said, adding that analysis is “hamstrung by a severe shortage of data”.

‘It makes us nervous’

It is possible that the process will not be as ferocious as many fund managers fear. “Most market participants are not betting on aggressive QT,” says Alex Veroude, chief investment officer (US) for global asset manager Insight Investment. “Nobody thinks central banks will start dumping hundreds of billions back into the market.”

But either way, most still fret that they have a weak understanding of where any stresses might appear.

“It’s not a given that it’s easily absorbable,” says Peter Rutter, head of equities at Royal London Asset Management. “It feels like we’re embarking on this in a rather casual way. ‘Yeah well let’s start it and see’. We’re watching very carefully. It makes us nervous.”

Bill Nelson, a former Fed official and now chief economist at the Bank Policy Institute, says the central bank does not intend to use asset wind-downs as a direct tool for influencing the economy. “They don’t want anybody really thinking or talking about the balance sheet . . . In order to achieve the tightening objectives that they’re seeking, I don’t think they would ever do that with the balance sheet.”

But he shares a widespread view that the exercise risks destabilising the US government bond market, the foundation upon which global markets are built.

“There is a lot of uncertainty about how things are going to play out on the Fed’s balance sheet and within Treasury markets over the next six months,” he says. “Part of the reason why they engaged in QE was to provide some support for the Treasury market at a time with very heavy borrowing, and that borrowing continues. Ultimately, everybody’s going to need to discover the capacity of the market to handle that.”

Episodes of dysfunction or misfiring transactions in the Treasury market seem like an inevitable outcome, even despite new facilities the Fed erected last year to alleviate pressure on the bond market.

“We are worried about what I think of as the eventual collateral accumulation on the street, just the increased amount of debt that needs to be held by the private market, as opposed to with the Fed,” says Mark Cabana, head of US rates strategy at Bank of America. “We do worry that that can have deleterious impacts on market functioning over time. It can likely worsen market liquidity.”

Exacerbating fears is the fact that Treasury liquidity is already significantly impaired, cratering this summer to its worst levels since March 2020, when the pandemic sparked a dash for cash and trading conditions for the world’s safest asset seized up.

Memories of the Fed’s last attempt at reducing liquidity are also still fresh. In the closing weeks of 2018, stock markets took a sharp dive after the Fed indicated balance sheet run-off was on “autopilot”.

“Remember that had a huge impact, and that was just on QT,” says one senior bond trader in London. “There was no inflation scare, no growth scare like we have now.”

Optimists in the fund management industry point out that without central banks keeping a lid on volatility and snapping up assets almost indiscriminately, the performance of asset prices will vary more widely, throwing up opportunities for money managers. “That’s healthy,” says Andrea DiCenso, a portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles. “I’m not sure it’s necessarily fun.”

But the habit of making bets with the Fed’s safety net below will be hard to break, she says. “People are thinking ‘I want to get back to QE. How do we get back to the QE?’”

Get alerts on US quantitative easing when a new story is published